I have a box of papers in my office that I like to look at every now and then; it's an archive of sorts, a collection of artifacts from what seems to me like an entirely different era of Paganism. The box contains old rituals, festival invitations, newspapers, zines, and even a few decades-old picnic leases for public parks, the sites of sabbats that were held when I was only a few months old. I am a child of the internet, and it can be hard for me to think of what "Pagan community" meant, exactly, in the time before it. But my box gives me a glimmer, sometimes.

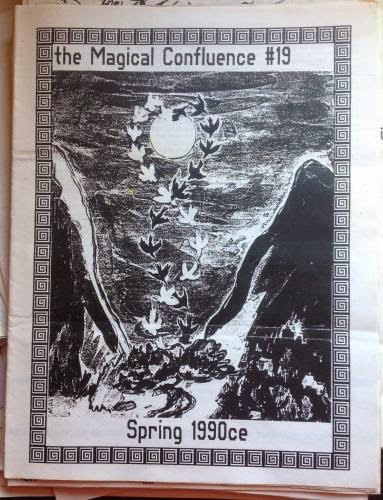

One of my favorite items in the box is a run of a zine, "The Magical Confluence, "which was published by the Earth Church of Amargi quarterly in the late 80s into the early 90s. The average issue runs about 16 pages, all black and white, most of the text obviously produced on a typewriter rather than a word processor. Clippings from local newspapers and national publications like "Green Egg" tend to make up about half of the content, with the rest submitted by Pagans in the St. Louis community. There are occasionally "Far Side" cartoons for which I am not entirely convinced Gary Larsen received royalties.

Looking through "Magical Confluence" #19, published in Spring 1990, I found an article by none other than my father - "AMER: AN OPPOSITION VIEW," an open letter published in a forum that reached, I'm guessing, maybe a couple of dozen people. He was weighing in on his general distaste for the Alliance for Magical and Earth Religions, an organization that tried to counter anti-Pagan misinformation through pamphlets, press statements, community meetings, and so on. AMER was founded in 1986 and lasted for twelve years before being disbanded. Despite his role as high priest of a long-standing coven in the St. Louis area, my father had little patience for community organizations; he compared AMER's attempts to bring him and his into their fold as being "bludgeoned with a club."

Much of my father's article is inside baseball to a local controversy that happened almost 30 years ago, and even after I asked him for context, I'm still baffled. (It was something to do with Satanists.) But there's a one section that I have been chewing over since I read it:

"If true that AMER's purpose is "to insure the individual's right to privacy" then why do you seem to be so hell-bent to convince me that I am wrong to abridge my right of free association. Free association, you understand, is not only the ability TO associate, but also the ability NOT TO associate. It seems inconceivable to some of you that there are individuals and groups who simply ARE NOT JOINERS."

Just that turn of phrase: "some people are not joiners." My father certainly isn't one - not just in terms of religion, but everywhere in his civic life. He has never claimed affiliation with any political party, never joined the PTO when I was younger, never been a part of an Elks Lodge or the sort. He "is" part of a union, but his career compelled him to join it. Even in his magical life, he eventually left the OTO exactly because it was too much of a "joiner" institution for him. If my father bowled, he would bowl alone. That inclination seems common in his generation of Pagans - and perhaps for many Pagans across the board. Our religions, after all, are made up primarily of converts - people who, for the most part, had a reason to reject the institutions of their parents. It's not really surprising that people who turned away from organized religion might prefer not to join organizations - especially those which try to organize their new, previously unorganized religions.

But - and I realize this is something of a refrain for me - I am not a convert; I didn't turn away from anything. And just like it can be hard for me to understand how publications like "The Magical Confluence" connected the Pagan community before we all had the internet, it can be equally as hard for me to understand the way that those who turned away see the world. I struggle with this. "Some people are not joiners. "Am I?

The covers to both volumes of Our Troth, from The Troth's website.

For Yule, my parents got me a copy of "Our Troth, "the handbook published by the Heathen organization The Troth. I haven't had the chance yet to read through it, as I'm in the middle of preparing to teach the entire history of British literature, but just flipping through the book has made me think again about joining the organization. It was a thought I had when I first started thinking of myself as a Heathen in addition to a Wiccan, and had only been reinforced by getting to know some of its members a few years ago at Pantheacon.

But I have never actually gone through with it, even though I see the obvious upsides - a connection to a larger community, the support of an organization that more or less aligns with my beliefs, and a pretty, pretty journal. I suppose part of the reason for my prevarication is that it could end up being an empty gesture - would it mean anything other than a stamp of approval, a sign that I am a Certified Heathen? The other part is the general philosophical stance I have inherited from my parents: "some people are not joiners. Some people," of course, means "us." We keep to ourselves; we do our own thing. We keep to the edges, because the edges are free.

I see a debate in the Pagan community - at least the one I can see from my tiny window onto the internet - about what direction we are moving in, whether it's towards more robust and public infrastructure or a move to remain with the largely decentralized nature of the movement as it currently is. I find myself, as ever, hedging about the middle. I grew up in the relative isolation of a handful of covens, and I know and love that environment; I also remember being a 13 year old kid who wished he could have just gone to a normal kind of church, except with Horus instead of Jesus.

My questioning over whether or not I want to join some organization is, I admit, a rather inconsequential element of that debate. But it's those little decisions that, ultimately, pull us all in one direction, towards one definition of progress or the other.

" Sic."

" My department's British Literature seminar is one semester, Beowulf to present. We go from John Donne to Oscar Wilde in about five weeks. I may keel over at some point."Send to Kindle